immediately before watching every single one of michael haneke’s movies in chronological order—in addition to countless interviews wherein the austrian filmmaker behind funny games, cache, the piano teacher, and a handful of other intellectually unsettling movies repeatedly explains in detail what his Whole Deal is—i coincidentally had an experience that served as a perfect prologue. walking back to my seat after using the bathroom at the back of a plane during an international flight i couldn’t help glancing at each of the individual tiny screens pacifying the passengers. more often than not the brief glimpse i caught of each of their TVs featured acts of extreme violence being carried out (or were likely imminent, as signaled by firearms casually being brandished) as the viewer looked entirely numb to what they were witnessing.

it was easy to pass judgment up until the moment i returned to my seat, crawled back under my gratis blanket, and resumed staring blankly at gangs of new york, a movie which famously opens with a fairly intense and surprisingly graphic melee scene in order to set up the next two-plus hours of simmering vengeance, and a movie directed by the man whose on-screen violence famously, depending on who you ask, played a role in an attempted presidential assassination.

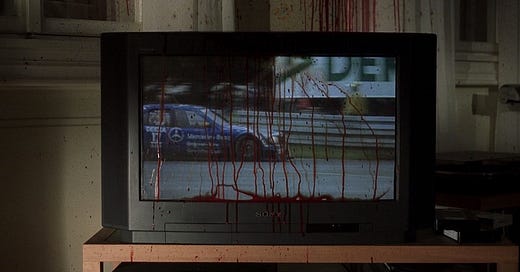

enter the first and primary tenet of haneke—a director who ironically is largely associated with the sadistically violent filmography he created specifically to address his concerns with how sadistic violence has pervaded popular media to the point of widespread viewer apathy towards it. it isn’t so much the issue that brutality has become so commonplace in pretty much all forms of screen media that haneke is concerned about as it is the issue that we accept that reality without a second thought (of course we need to see leo’s dad bleed out in order to be convinced his epic-feature-film-length rage is justified; also, many of us do have a second thought: wow this violence looks good and cool!). while it should be noted (as he seems to in every interview he’s done since the late ’80s when he leveled up from directing TV movies in his native austria to feature films) that almost all of the violence in haneke’s movies occurs offscreen, it’s even more important to clarify that this violence occurs in the first place in order to allow him to address it. sometimes directly into the camera, through a surrogate character.

these metatextual discussions on violence are so vivid that upon rewatching many of his movies (funny games in particular) i was surprised to find out that i (along with many others, as haneke also notes in many interviews) had mandela-effected violent scenes into several of them, likely as the result of the films’ psychological intensity nearly equating with the intensity of physical screen violence. in a similar way, i was impressed returning to these movies to find that haneke is fairly nonjudgmental towards his audiences, instead mostly placing the blame on hollywood and the media and the way they wield visual information technology—condemning these entities in each of his films as aggressively as he condemns liberal-elite couples named georg(e) and anna(/e).

outside of his movies, though, haneke is a bit less kind when it comes to addressing his audiences, particularly those of us whose diets include hollywood fare. as sharp and relevant as he’s remained across his three-decade film career when it comes to addressing media depictions of violence and how they contrast with real-life examples of it—both in his movies and in interviews—his anti-hollywood sentiment always feels a little narrow-minded if not downright condescending, betraying the fact that he’s among the category of intellectuals who, in the classic hinkley finger-pointing case, would put the blame on scorsese for his behavior (or at least wouldn’t absolve him). having grown up before the era of widespread screen literacy brought on by the domestication of TV it seems like he underestimates just how good younger generations have gotten at watching screens.

throughout the two post that will follow in this series i’ll occasionally be referencing hollywood (or otherwise american) films released nearly concurrently to haneke’s own oddly similar features, which he never seemed to address and which explicitly take shots at the same facets of violence and/or screen media that is his filmography’s central thesis—parodic commentary of sadistic horror in funny games and scream a year prior, for example, or cache echoing a history of violence’s layered allegories for repressing the guilt of evil deeds.

one title he does publicly take exception to is natural born killers, which arrived at the tail end of haneke’s ‘glaciation trilogy’ (the seventh continent, benny’s video, and 71 fragments, all of which implicitly address the intersection of murder/suicide and television consumption), and which he views as a fascistic approach to condemning our culture’s over-saturation with violent news clips. ‘in film as soon as you’re too specific, you allow the audience to escape,’ haneke quipped in (at least) one interview, both explaining the appeal of his open-ended narratives and alienating the type of audience who’s drawn to the leftist parables of gruesome politicized violence oliver stone once specialized in.

if you’ve seen pretty much any of haneke’s movies, though, you know that he prefers to approach this type of violence in a way that’s more slyly direct and uncomfortable: by implicating the middle-class viewer, the target audience for his filmography, through our identification with the morally passable white liberal family that serves as the archetypal subjects of each film. by the mid-2000s, it became pretty clear in his recycling of the names ‘geroge’ and ‘anna’ for each of his lead characters that they were less written as flesh-and-blood vessels for empathy and more as voodoo dolls for haneke to puncture with the social ills of austria, france, and any other nation far enough removed from the genocidal scenes playing out on the characters’ newscasts that they no longer bat an eye at such reports.

which brings me to my last point, a full-circle callback to my opening anecdote, and the second tenet of haneke’s central thesis (we’ll leave the shockingly omnipresent throughlines of suicide and family members slapping each other—the latter of which, if you’ll indulge me in addressing this specific action (which, in my count, occurs in 9 out of his 12 theatrical features), serves as a great on-screen metaphor for what it feels like haneke is doing to us, the audience).

the flight i previously alluded to took place on october 7, 2023—notably the day the hamas/israel conflict began its escalation to its present dire state of blatant genocide aided by the U.S. and a majority contingent of first-world allies. the flight attendant broke the news over the PA before we landed for those of us who didn’t take advantage of the airline’s wifi service (not gratis)—though i don’t know how many passengers were listening, considering some of us had timed our expendables to end just as we were making our descent. it’s the perfect haneke scene: a random sampling of middle-class inhabitants of the first-world brought together by a shared sense of guilt, apathy, or obliviousness—or all three, who can really tell?

and i’ve felt like i’m living in haneke’s universe ever since. i cringed through a week of NBC nightly news broadcasts while back home at my parents’ house over the holiday as lester holt’s vacation-days surrogate not only presented updates on palestine with an infuriating slant, but did so with as much depth as two-minute time slots can provide before wrapping things up every night with what was almost literally a puppies-and-flowers, feel-good small-town report meant to offset 25 minutes of transparent ethical apocalypse.

shortly afterwards i caught zone of interest in theaters just after wrapping this project up, and the pre-movie footage alamo drafthouse curated specifically for the screening jarringly transitioned from holocaust stories to jonathan glazer music videos specifically recreating iconic images from the horror-violence of the shining and clockwork orange—to say nothing of a movie about ethnic cleansing being immediately preceded by a trailer for the zendaya two-boyfriends movie. incidentally the next day nancy pelosi went viral for saying some evil shit about pro-palestine protestors that felt molded from the exact same brain rot exposed in this movie.

and in the meantime i’ve been piecing together the full story on palestine every day from on-the-ground reports shared on social media by mutuals such as one particular friend who consistently shares both devastating statistics on the genocide and some of the most expertly curated memes within the same instagram story every day, usually quite intermixed. because in our screen-manipulated culture it’s increasingly rare that you can have one without the other. and it’s making everything very, very confusing.

in the coming weeks, i’ll be sending out follow-up emails with words on haneke’s full filmography (17 movies between film and TV work, plus bonus features) divided up into four parts, two in each email, with brief intros providing some context to each section. in the meantime, i included all of the visual and literary accompaniments i relied on throughout the process of screening these movies below.

and for those uninitiated with haneke, may i recommend his bio on the great film resource wikipedia dot com. i guess the only thing you really need to know about him is that his stepfather literally married christoph waltz’s mom.

field guides

VISUAL

tom jones dir. tony richardson (1963) to be honest i didn’t watch this movie but in every single interview i watched or read that discusses his childhood he cites it as an early cinematic awakening—specifically a new-wave-y moment where albert finney directly addresses the audience in the middle of a chase scene. seems like he’s been trying to get revenge on screen media for its growing disdain for the fourth wall ever since.

24 realities per second dir. nina kusturica & eva testor (2005) collection of verite BTS footage spanning time of the wolf’s production and a bit of cache’s that mostly focuses on haneke’s on-set behavior and his interactions with journalists, photographers, and audiences with occasional in-transit shots featuring some questions coming from behind the camera. pretty much exactly what i’m looking for in a doc on a filmmaker—it never tries to inject its own narrative or pay homage to its subject, as these things tend to do, and as another filmmaking crew would later do with a more feature-film-length project a decade later.

michael haneke – my life dir. felix von boehm & gero von boehm (2009) hour-long TV doc covering the biographical basics which hardly come up in anything else i watched or read while focusing on white ribbon. plenty of (very funny) childhood pics and a weird amount of focus on haneke talking about his fear of violence—not to mention interviews with juliette binoche being like ‘yeah man he’s really afraid and also a lot like a child.’

BOOKS

the cinema of michael haneke: european utopia edited by ben mccann and david sorfa (2009) i’ve read nearly a dozen books in this series and while there’s always plenty of worthwhile info in them they always skew just academic enough that i frequently wanna put it down. on the one hand this was the only book i read that acknowledged the U.S. funny games remake; on the other one whole essay is almost entirely just a pastiche of levinas quotes.

contemporary film directors: michael haneke by peter brunette (2010) far less intellectualized interpretation of haneke’s movies up through the white ribbon with most of the chapters predominantly walking through the plots of each movie—which is more interesting than it sounds, considering haneke’s films are so abstract that i (and the authors of the others texts i read) had conflicting interpretations of what we considered to be objectively true about certain plot points. also made me realize that brunette and the other authors i read have very little knowledge of quote-unquote low culture—none of them come close to correctly identifying the realm of music john zorn’s track in funny games falls under, and clearly none of them have seen toxic avenger, one of the movies benny watches in benny’s video.

michael haneke: interviews edited by roy grundmann, fatima naqvi, and colin root (2020) even though he tends to repeat himself quite a bit, haneke is a really great interview subject—as much as he pretends he’s the type of director who won’t give anything in his painfully abstract movies away, he then immediately holds our hand through every detail of the movie and corrects the interviewer if their interpretation is off-the-mark (but then also reassures them that his movies are all very abstract and there are no answers!). this one’s additionally important since it’s the only book i could get my hands on that includes all the movies up through happy end.