prologue to the best albums of 2005: some, uh, mentions

(drake putting his hand up/frowning) “post-punk revival”; (drake pointing/smiling) “dance punk”

it’s gotten so easy to lump all the mid-2000s indie rock albums together, but it’s actually shocking how much of a difference a single year makes. last year around this time i published a list of albums released in 2004 that i feel a certain nostalgia for—good albums that i still enjoy, bad albums that i still enjoy, objectively silly albums that were at least fun to revisit. the majority of the list was made up of post-punk revival, garage rock revival, and a number of other brooding, recycled, and guitar-centric subgenres, along with a couple pop-punk records to add a bit of context for what was going on in adjacent corners of the alt-rock scene.

in taking on a similar task this year, it became immediately clear that all of these bands were funneled into roughly the same “dance punk” category at this point in time—basically the exact same drum and bass parts paired with misogynistic lyrics and a surprising amount of the-edge-homaging guitar that all but guaranteed the artist a spot on the MVP baseball 2006 soundtrack. revisiting these albums every few years inevitably leads me to feel nostalgic, but at the same time there’s this parallel sense of being unable to tap into the ignorance of my teenage years that once permitted me to enjoy certain lazily reheated elements that define a lot of this music. at the time i looked down upon a lot of my friends for buying into pop-punk, which was more overtly commercialized in my hometown than indie rock, but i can now more clearly see the ways in which indie was clearly a commodity carelessly being schlepped to boost sales for Big Skinny Jean, who maybe should’ve reached out to lil wayne a few years sooner.

there are certainly some examples of dance-punk albums from this era that stand the test of time, that had plenty going for them beyond their catchy grooves (and, often, in spite of their obvious hail-mary attempts at scoring future ipod commercials), but i don’t want to talk about those just yet—instead, this initial issue of a three-part series on records from 2005 is devoted to the albums that fell out of my rotations years ago for any number of reasons. many of these titles, as it turns out, are very bad; as an adult, i can confidently say that i have a better sense of what’s “good” and what was merely presented to me as being compatible with the personality i was trying to cultivate for myself, whether because it was the work of a prominent band within a category of music i almost exclusively listened to or because they were virtually unknown (stateside, at least) within that same demographic.

in any case, i or someone in my family dropped $10-20 on each of these albums, so i believe that entitles me to write anything i want about their creators. probably not what my financial adviser meant by “investing in CDs,” but boy did they pay out!

death cab for cutie, plans i’ve always viewed this album as the defining bipartisan statement from the precise center of the mid-aughts alt-rock divide—a high-profile work as impressively noncommittal as taylor swift’s political views with its too-evocative-for-indie lyricism and not-whiney-enough-for-emo vocals. like most major-label rock debuts from this era, plans still feels rooted in the scene it emerged from, only with an exaggerated emphasis on their singer’s broadly-appealing vocals. the result is something like pinback if they were fronted by a variation on colin meloy that never got into after-school extracurriculars and instead spent evenings meekly strolling through the mall in the off chance that he’ll run into his crush, despite not knowing whether it’ll be at hollister or hot topic.

i think the two main reasons i was never really won over by ben gibbard are unrelated to the mid-’00s emophobia that defined my high school years. for one thing, he was writing poetry when all the stuff i liked at this point was dumb-guy rock music. for another—and i know this may not be objectively true—death cab always felt like a singles band to me. this album mirrors good news for people who love bad news in several ways, and if i may be so bold as to talk about plans the same way many of you discuss that album, it feels to me like clear-cut radio singles padded out with fairly generic filler that i imagine was an affront to the band’s barsuk-era listeners.

there are a few album tracks that stand out to me, like “your heart is an empty room” with its weirdly edge-inspired guitar part, but this album only gains momentum with the appearances of its properly rationed-out singles. “i will follow you into the dark” feels a little up-prologue to me in retrospect, though the nada surf appreciation that is “crooked teeth” hits like a welcome breeze after a particularly dark stretch late in the album.

death from above 1979, romance bloody romance (remixes & b-sides) as a continuation of the appreciation i wrote for you’re a woman i’m a machine last year, this compilation was my initial introduction to the fact that the punk rocker i mistakenly believed myself to be while listening to that record shared DFA’s loyalties with the electro-house scene. as its title suggests, the comp balances the band’s scuzzy B-sides with remixes seamlessly repurposing YAWIAM’s songs (well, mostly just “romantic rights” and “black history month”) as repetitive bloghouse ravers courtesy of a guest list including justice and braxe & falke and less-expected figures such as josh homme and owen pallet—not to mention jesse keeler’s own MSTRKRFT project he headed alongside the pure-cut hardcore-punk outfit femme fatale.

which maybe would’ve been fair to both demographics they were evidently playing to if it wasn’t for the fact that this thing is so heavily weighted towards dance music. it opens strong with a cover of an obscure ’70s punk band before switching gears for the next 30 minutes, until we get the album’s second and final B-side: the original track (fundamentally DFA, given the indie-sleaze misogyny inherent in its title) “you’re lovely (but you’ve got lots of problems),” which is easily the worst thing they’d written before re-banding again in 2014. and that’s it. another 25 minutes of shitty nu-disco follows, omitting “we don’t sleep at night” from the romantic rights EP (perhaps too rough for such an otherwise-polished release), as well as the band’s “luna” cover from labelmates bloc party’s silent alarm remix album—which is so good that it always made me want to check out the rest of that compilation before remembering how badly i’d been burned before.

the decemberists, picaresque keeping this one short because, as i realized last year while blurbing the tain EP, i can’t manage to talk about this band without putting my older brother on blast, as he was very much the target demographic for this band when they hit peak dark-cabaret, which for some reason was a very popular aesthetic in the period between moulin rouge! and the launch of married to the sea dot com. this album features some of the decemberists’ most appealing (or even just harmless) acoustic folk music for the pre-playlisting indie trough, as well as some of the most insufferable shtick the band ever produced with phrases like “vast veranda” and pronunciations such as “betrothèd,” as well as broader affronts like the nine-minutes-in-hell that is “mariner’s revenge song,” which immediately cancels out the album’s most enjoyable 10-minute span.

despite continuing to wallow in the theater-kid comforts of baroque-pop compositions, rushmore invocation, and 1920s-jock cosplay, their prog aspirations do seem to shine through a bit in some of the denser and/or longer pieces that feel particularly attuned to detail. i guess the crane wife was just around the corner, but it would’ve been nice to see that side of the band win out here against the straightforward pop of the album’s lone single “16 military wives,” an anti-nationalist anthem somehow even more unassumingly political than “tubthumping,” and “the sporting life,” which for some reason replicates the entire percussive base for iggy’s “lust for life,” which was soundtracking royal caribbean cruise commercials at this particular point in time.

gorillaz, demon days there are things i appreciate about this album that i hated as a kid and there are things i hate about this album that i appreciated as a kid, and what it all comes down to is the perception of gorillaz as the artistic venture of rogue cartoon characters in a pure, pre-AI world versus the reality that it’s just a major britpop figure successfully how-do-you-do-my-fellow-kids-ing his way back into relevance via hip-hop’s then-recent radio takeover. as a teen i was totally oblivious to the sheer amount of industry connections demon days signifies (ike turner? neneh cherry? dennis hopper?) even before the project’s blatant foray into A-list features, while for some reason albarn’s vocals made so much sense to me when they were attached to an irisless animated punk and are beyond grating now that i immediately recognize them as those of the woo-hoo guy. i guess it’s the donna chang effect (ehh, maybe don’t google that).

like many kids of my age and background, i’m sure, gorillaz was a huge door-opener when it came to getting into hip-hop, and as an adult i wonder if albarn’s blandly melancholic vocal presence may have hindered a similar interest in trip-hop and dub sounds. it’s always been bootie, de la, DOOM, roots manuva, and danger mouse who most appealed to me about this album, but as an adult i can’t help focusing on how much the presence of albarn and his peers (e.g. the happy mondays guy on “dare,” a song i could not believe belonged to gorillaz after i was introduced to the project via “clint eastwood”) drag me out of this wildly unique world they built for me (i at least feel vindicated that others have picked up on this weird dynamic). i’ve come around to the instrumentals on “last living souls” and “every planet we reach,” but it’s hard to live with the fact that it isn’t del the funky homosapien soliloquizing about robot labor or whatever over them.

gym class heroes, the papercut chronicles maiden release from pete wentz’s label that oddly balances the massive mid-aughts appeal of hot topic in its lyrics/artwork against funk-laden punk-rap that lands somewhere between sublime’s reggae rock and a version of flobots that’s not only apolitical, but seems to look down upon progressive ideals (“i’ll let these protestors picket like they’re gonna make a difference / and watch them die before they realize their cause was non-existent” ???). way slower than the album they became most well-known for and almost entirely devoid of its fun, despite sharing a baseline double standard of empathizing with bullied kids while doing plenty of punching down themselves. truly the tony hawk’s underground to cruel as school children’s THUG2.

maybe this all makes sense when you consider that this is essentially a concept album about doing pills, with the occasional freestyle allowing travie to break through the doldrum haze. although it’s far from the pop hit it would become post-makeover, this original version of “cupid’s chokehold” is at least jauntier than everything else on this album (though still pretty drained of color), while “taxi driver” cleverly recreates the teen pastime of doodling band names in different fonts in the margins of your class notes. i had absolutely no recollection of mr. dibbs remixing the former track and am shocked that it was thrown onto the album proper as it begins to disintegrate into bonus material at the end. was this the most exposure anyone from the anticon extended family had received in 2005? maybe ever?

hard-fi, stars of CCTV on the one hand, hard-fi felt like a refreshingly socially-conscious break from the mopey indie rock of the era. their debut album opens with a cash-strapped homage to the clash before becoming openly critical of US-forged military operations on the punkier “middle eastern holiday,” while the closing title track takes the form of a cheekily balladic middle-finger to surveillance society. it’s all very andrea-arnold working-class angst on its fringes, but the other side of the stars of CCTV coin reflects the undeserved amount of hype they received, leading to its sagging midsection falling prey to sob-story lyricism and orchestral flourishes (well, synths, i assume) that lowest-common-denominate their otherwise rough-edged sound that comes through much clearer on the album’s B-sides and remixes (which include a full-on reggae-rock cover of “seven nation army” that sounds a whole lot more comfortable than most of these songs).

evidently this album has aged into the UK version of that tom brokaw book you see at every thrift store here in the states. it doesn’t seem to be fondly remembered over there and it seems to be entirely forgotten here, and i wonder how much of that is the band’s fault. sure, the singer’s lack of charisma while delivering panicked lines like “oh no my girlfriend’s test turned blue” makes certain moments fall flat (arctic monkeys showed us how to make that vocal style work a year later), but it seems to be the songs that place them in the purgatory between well-produced dance-punk and messy garage rock that weigh this thing down. “gotta reason” sounds like it was written for the hives, while “move on now” was almost certainly penned with a gun to the band’s head from label execs looking to capitalize on this coldplay thing. i don’t even know where to begin approaching their breakout single “hard to beat,” which transforms from landfill indie into awkwardly placed french-disco propulsion during its chorus.

hot hot heat, elevator hot hot heat is possibly the most tragic tale of victimization at the teeth of the indie-rock machine, a story of quick devolution from legitimately fun maniac sasscore to being totally swallowed up by a steadily increasing production budget until you can barely make out their half-assed mod-pop aesthetic under 40 layers of steve bays’ deeply unpleasant vocals. it occurs to me now that make up the breakdown really only appealed to me for the paradox of its pop aspirations and its playfully knowing sense of messiness, buoyed by a genuine earworm like “bandages.” all of the indie rock releases from this era contained at least one such try-hard single gunning for soundtrack placement, but every single song on elevator sounds that way to me, adding a certain layer of irony to the marionette-band album cover.

i was never a huge fan of this one as a teenager, though songs like “jingle jangle” and “pickin’ it up” never grated on me quite like they do now—the former seeing bays embody some dylan-esque waif throwing kids down a well or something, the latter’s self-satisfied wordplay syncing with an instrumental that sounds like springsteen if the blue-collar work that fuels his music was swapped out for the guy i used to see on the street in wicker park stooped over a typewriter trying to sell his poems, dressed like the google results for “poet clothes (contemporary).” the album’s actual single “goodnight goodnight” is exactly the type of cocksure outgrowing-a-relationship indie-rock song that could only be written by someone who thought their blossoming music career would sustain them at least until their next album—which, in the case of hot hot heat, would be a comically dejected being-broken-up-with concept album titled for the lyrics “happiness is limited / but misery has no end.”

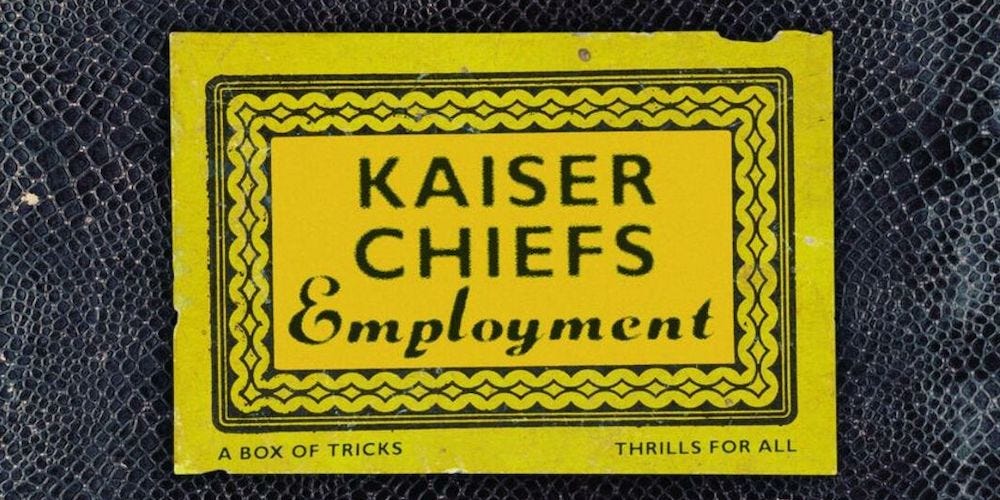

kaiser chiefs, employment i’d never made this connection before, but it occurs to me now that everything i find offensive about kaiser chiefs also happens to be everything i just dunked on elevator-era hot hot heat for: the unbearable vocal timbre and inflections, the uninspired blending of power-pop and overproduced garage-rock-revival dregs vaguely leaning into a vintage rock-and-roll aesthetic, songs about hating the person they are or potentially could be dating. casual usage of terms like “emotional abuse” dot the genius entries for songs as innocent-sounding as “you can have it all”—there really was an epidemic of dorky songwriters taking the “tired of sex” schtick too far during this era.

kaiser chiefs kind of feel like aughts NME-core’s “she’s so crazzzzzzzy love her” band, a one-trick pony who’s only trick—going “woooah, wooooah, WOOOOOAH, WOOOOOOAH” on almost literally every song—sucks. obviously their whole thing is more consciously post-britpop than HHH’s (the piano on “oh my god” even whiffs of a premature madchester revival), with their singer (his name is ricky; of course his name is ricky) generally sounding like a congested morrissey doing jack black’s exaggerated classic-rock vocal routine with a stifling sense of irony.

evidently they reached a tier of success with their debut album beyond the coveted O.C. soundtrack placement with several songs even appearing on those NOW comps—maybe that makes sense when you consider that at worst their lyrics embody republican urban anxieties and at best feel like high school literature coursework with passages underlined next to the word “society??” written in the margins.

OK go, oh no my recollection of this album was that it stands firmly on its own feet, that the band’s music video gimmickry was embarrassing and totally unnecessary, that they should’ve severed that performative aspect of the project from the music itself. but listening now, it sounds like music made by four guys who refer to themselves as “gentlemen” in the studio. it sounds like a band who seemed a little too eager to beat the geek-rock allegations of their debut with a more muscular follow-up on which they still can’t help including irritating flourishes like throwing a backing-vocal “one zero zero zero zero zero zero” behind the title lyric of “a million ways”—possibly the worst facet of the character they displayed on the glammier self-titled as the rest of their sound gets sanded down to target-commercial indie-pop made by men who clearly bought their suits at that precise department store.

of course what stands out here is the question of whether “here it goes again” betrayed these guys’ real desires of winning the internet, good sir, and becoming youtube stars before that was really a thing, rather than being an indie-rock success story, in which case their singles might well have been written around their treadmill choreography rather than vice versa. i can still hear what i used to appreciate about this album in the unapologetically rock tracks like “it’s a disaster” and “no sign of life,” though it’s the power-pop backing vocals suppressed under these party songs made by people who clearly weren’t being invited to parties that i now wish shined through a little more. also, i’ve never actually listened to the 35-minute field recording that closes the album—for all i know, that redeems everything else.

the white stripes, get behind me satan it’s kind of fascinating to think about how jack white’s trajectory directly mirrored that of johnny depp’s in the early 2000s as he, too, sold his soul to the devil—not for talent, which both weirdos already had plenty of, but instead for, like…rings and really stupid hats. and maybe placement on a commercial for american-made trucks or husky-fit jeans for men, in white’s case.

get behind me satan feels like some odd purgatory in this midst of this transformation, between the white stripes’ willingly sloppy garage rock and the high-concept, capital-R rock stuff jack was secretly actually enamored with, but evidently unable to fund on their first four albums. it feels like a sophomore record after a band gets poached by a major in its near-comically unfocused nature, even if the few post-production flourishes get buried in gospel, straightforward blues, some of the band’s most o brother ass trad-country they ever recorded, and wall-to-wall piano nearly supplanting white’s guitar as his primary instrument.

the chasm between the heavily misleading metal riffs on opener “blue orchid” and the pop-chart aspirations of lyrically-overstuff and therefore accidentally-kind-of-rapped singles like “my doorbell” and “denial twist” would suggest meddling by a label trying to cover as many demographic bases as they can if it weren’t for the fact that all of this feels entirely like the doings of white’s fingers, weighed down by all of those evidently just metaphorical rings.