part 1, ICYMI

10. melkbelly, pennsylvania looking back, it couldn’t have been a coincidence that i finally fell in love with chicago’s music scene the exact moment i moved to LA in 2017. after seven years of going to shows and getting to know local openers like netherfriends, outer minds, showyousuck, and BBU—who seemed buried under the hype being generated by the smith westernses and chances the rapper suddenly putting the city on the map again for the first time since wilco and kanye—it wasn’t until i got into records by nnamdi, lala lala, and dehd while living in a city where none of these bands were playing that i perceived any sort of local identity in each of these unique artists, which clashed with the broad network of mostly expatriated musicians in LA.

i recall learning about melkbelly sometime around 2014 when i saw them open a show, but it wasn’t until their debut album nothing valley dropped in 2017 that i fully learned to appreciate the way their music straddles the line between quote-unquote indie rock and the type of noise rock that feels like a furious response to that precise category of music. their pennsylvania EP, for example, opens with the sounds of percussive art-pop—bringing another local peer of that era to mind, anyone remember a lull?—before introducing their signature fucked-up snare sound that instead invites comparisons to the free-form weirdo-prog of lightning bolt. i can see how the psych-y drive of “doomspringa” and the band’s tendency to sing about, like, kissing under some bats or whatever scratched the same itch that i generally relied upon “thee oh sees” era oh sees to cover.

the stretch on pennsylvania that wound up being most characteristic of the band is the transition from the almost mockingly straightforward indie-rock of a near-interlude track called (and about) “highway meat” into the doomy, heaving metal and unexpectedly shrieked vocals of “theme from blar.” by this point it’s far from surprising to hear the record close with eight and a half minutes of subtle yet still jarring tempo changes under sharrock-tier riffing. all of it’s as bold as what nnamdi was doing with hip-hop (and the letter O) on dr00l, or as unique as lillie west’s chicago-by-way-of-LA-by-way-of-london vocal affect on the lamb. “i feel like in chicago people are just making art for art’s sake—for their friends, to enjoy themselves,” west told me when i interviewed her in 2018.

i can’t tell if i’m prouder of my home state of PA for inspiring this demented EP or of my adopted hometown for pumping all these bizarre ideas into the creative water supply, permitting it to come to fruition.

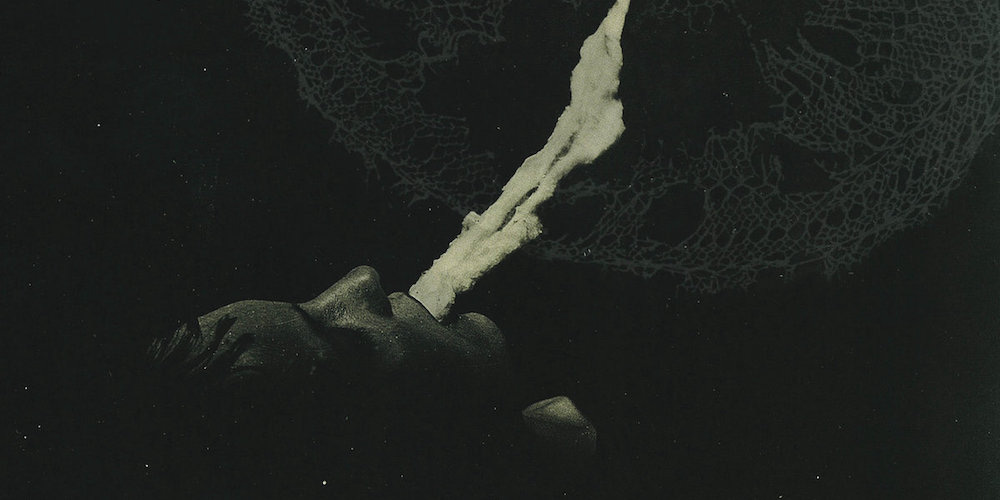

9. white suns, totem as formative as bands like deafheaven and yellow eyes were for me in the mid-’10s for getting into metal, white suns were equally important when it came to setting me on the path toward all the evil shit i’ve come to appreciate—“evil shit” being a non-genre denomination that includes portrayal of guilt and full of hell and the flenser and death-industrialism and post-yow noise rock and any other sound that harnesses pure human dread and efficiently transforms it into indescribably manic rock and/or electronic music. the no-wave ethos of white suns certainly leant itself to this concept, their pop-group-by-way-of-big-black-and-throbbing-gristle-and-maybe-even-daughters schemes coming to a head on totem with terrifying sound design that sees guitars used as a new form of horror strings as they squelch during the quieter stretches and recall radiators being bashed with a metal rod during some of the louder ones.

yet the record’s arrival during the swans-aissance doesn’t necessarily align them with michael gira’s vision for the aesthetics they shared. in fact totem generally feels like the opposite of to be kind, with that album’s infuriatingly patient monotone being swapped for erratically lurching noise that refuses to hit a groove for too long. there’s something much more analogous to jazz here as the four-man combo sounds both perfectly in-tune with each other through every hairpin turn of sound and emotion, despite the improvisatory feel those moments suggest. yet it also feels totally feral in the way tom waits does among blues music—it’s the framework of jazz modified to be paired with waking nightmares rather than poetry; in lieu of tea and heroin it feels entire fueled by PTSD and sleep paralysis.

it was a bit frustrating when the band returned three years later with an instrument-free record of pure power electronics that closely aligned with swans’ idea of typical track lengths, even if psychic drift was nearly every bit as powerful of a listen as totem was. yet in the years since, they’ve slowly and methodically been bridging the gulf between these two records with every successive release, in doing so showing us how similar these albums always were given their mutual evil-shit quotient outlined above. as much as i enjoy the first 25 moments of totem, it strikes me now that they could’ve taken their dread-ambient in any direction as long as it still led up to the absolute final boss of bad-trip rock and roll music that is “clairvoyant.”

8. cloud nothings, here and nowhere else in case you weren’t there for it when it happened, i recall the cloud nothings hype hitting in two distinct phases: the first positioning dylan baldi as the wunderkind figurehead of a premature-by-a-decade power-pop revival leading up to the hard-flop release of his band’s self-titled debut in 2011, the second—taking place a year later, to the day—as a figure of post-hardcore vengeance, bringing steve albini into the mix like a kid who got beat up at the playground returning to the scene of the crime with his yoked uncle.

maybe it’s not surprising that i never fully connected with attack on memory, given that i’ve never quite comprehended albini’s genius, but here and nowhere else always felt like the vastly superior album to me. working with the same palette of throat-shred fury and cathartic easing of post-hardcore tensions, it seemed to be received as one of those diminishing-returns records artists tend to release a curiously short amount of time after their previous album, as if throwing together some scraps from those sessions and feeding them to listeners as a main course. but rather than stripping its predecessor of its songs’ personalities, nowhere molds its heavy emotions into something quite different, something that feels closely descendant from source tags & codes. the fast and incredibly defined drumming across the album, in particular, feels inspired by jason reece’s work on “it was there that i saw you.”

another difference between these two records is that nowhere possesses more range and exists further outside of genre constructs, with baldi’s voice generally either reminiscent of the sedated aughts indie vocalist or a screamo-band mclovin prone to voice-cracking. i never quite caught the connection to emo when i was first listening to this, but revisiting PUP’s debut led me to understand how this may have helped pave the way for whatever wave of the genre we were on the verge of at the time, which gave us bands like prince daddy & the hyena, who balance raw emotionalism with manic bursts of post-hardcore energy without necessarily dipping into the well of established emo sounds. relatedly, i feel like bands within the exploding in sound orbit like kal marks wouldn’t have become what they are today without this album.

i haven’t really kept up with cloud nothings over the past decade, but it seems like somewhere along the way they managed to fuse together this harsher period with the prior power-pop stuff. which, hell yeah, that sounds cool. but i don’t think anything else they’ll do will live up to the juxtaposition of the tough, epically downward-spiraling “patterned walks” giving way to the oddly upbeat closer, a total-dissociation riff on the serenity prayer that’s increasingly muddled by the transitive property.

7. caddywhompus, feathering a nest which artists do you feel you’ve taken most for granted? i’m thinking frank ocean types who were such impressive figures for such brief periods that it felt like a lifetime between album drops, though in reality it turns out it was only a year or two. at this point i can barely fathom living in a world where another caddywhompus album is a possibility, though over the course of nearly a decade we got five perfect releases within the nebulous space between EP and LP that only further solidified their uniquely noisy approach to midwest emo, or their uniquely earnest take on the ever-jokey world of math rock. it’s hard to believe they’ve only been MIA for seven years.

in an era of power duos as defined by the muscle of japandroids and the endless tinkering of no age, each caddywhompus release felt defined by its ability to experiment further with heavy/soft dynamics—seeing how far they could bend their sound without breaking it. by feathering a nest, they felt like a more in-control palm, or a proggier krill. the record dabbles in the same twinkling guitar work algernon cadwallader was beloved for in between drowning that sound out with unexpectedly powerful riffs and atmospheric passages that reflected vocalist/guitarist chris rehm’s side-hustle as an architect of remarkable ambient lo-fi music. rehm’s echoey vocals feel spectrally manipulated in a way that brings to mind his NOLA DIY scene peers sun hotel, despite those two groups’ similarities abruptly ending there.

building upon 2011’s the weight, feathering revolves around instrumental ebbs and flows in the same way a lot of post-rock does, albeit with the dull stretches of quiet noodling swapped for more guided guitar grooves and the emotional peaks heightened with a more maximalist payoff. i recall them releasing “stuck” as a lead single, something of a trojan horse harmlessly introducing their safe brand of indie-pop as if the record it was housed within wouldn’t see the track seep into the deeply gnarly “company,” a track that almost feels like a serrated take on wall-of-sound-era girl groups as its refrain of “i’m your dream lover” gives way to one of the biggest drops in the band’s short career. from there, the brief “thirst” packs some of the album’s beefiest riffs, and the 10-minute closer feels like a victory lap as it juxtaposes their spaced-out improv and totally decimating shredding.

maybe this is why i’ve had a hard time getting into many of the above-mentioned points of comparison: palm and krill feel like watered down caddywhompus to me, while a band like japandroids never quite seemed aware of how far they could stretch their wings. i can’t help but think about current projects like chat pile which, to me, possess a similar ability to make anything they touch sound entirely their own and deeply compelling just based on their members’ individual talents and their undeniable chemistry together as a group. i hope they stick around longer than caddywhompus did, but for now i’ll continue to live within cool world as if it’s their final statement.

6. swans, to be kind in 2014 i began the first and only thomas pynchon book i’ve ever read, vineland, and i hated every moment of it. that is, until i completed the book after several hiatuses when i seriously contemplated giving up before convincing myself it had to have some redeeming quality in store by the end. it didn’t, but i realized that i’d never immersed myself so deeply within a novel before through an extended length of exposure to it. around the same time i also watched the 7+ hour satantango—a different type of punishing longform media—as well as david lynch’s giddy extended experiment in digital filmmaking, inland empire, which both provided the same nearly psychedelic feeling of detachment from reality.

i also heard my first swans record that year, the two-hour to be kind. it’s a project that actually lands squarely in the middle of pynchon’s over-the-top kitsch, bela tarr’s brutal monotone, and lynch’s improvisationally assembled nightmare. as much as i loathe the over-usage of “lynchian” to describe anything that’s a little spooky and/or folksy, it certainly applies here as the sensation of slowly sinking into michael gira’s morose aesthetic is almost entirely lifted both conceptually and sonically from the extended roadhouse sequence in fire walk with me. i don’t mean that as a dig, but rather as a compliment—lynch is among the most singular aesthetic visionaries of our lifetime. few people understand how he achieves the ineffable sense of dread that permeates his work, which has lead to an endless wash of superficial copycats that clearly don’t have the juice.

aside from these literary and cinematic reference points, i really had no context for this album when i first heard its lurching, misanthropic, cow-punk take on no wave, its unexpected frills in the form of church bells and what sounds like loudly sawed wood, to say nothing of gira’s constant fucked up incantations. i hadn’t seen any documentaries on NYC’s art scenes in the ’80s by this point, so i had no concept of the surreality of swans’ existence as the ghost of the no wave scene who improbably lived to see a cultural resurgence of art-pop after the grunge era, picking up elements of both of these movements along the way. this band shouldn’t have still been around in 2014, let alone blown up the way they did with 34-minute songs and a frontman frothingly insisting that his name is “fuck”—another lynchism in its invocation of frank booth.

even if such epic song lengths are part of what’s drawn me to metal over the past decade, swans feels like that genre’s opposite: meandering noise rather than driving, precise sounds. i do think there’s a connection between this music and doom metal, given that that genre similarly presents a contradiction of small sounds being amplified to feel impossibly large. it feels like the intention with this album was to instill that realization within the listener slowly over the first hour of music before giving way to the more experimental tracks: disc two’s gentle “kristen supine” and its transition into the manic peak of “oxygen.” i don’t hear anything particularly profound in the lyrics along the way. instead gira’s vocal inflections serve as another instrument dredging up a sense of dread—perhaps the most affecting, given that they’re the most recognizably human.

another longform piece of media i’ve engaged with more recently is where does a body end?, the 2019 documentary about swans that fuses together origin-story biography with concert footage and talking-head interviews. above all, though, the doc seemed like its aim was to mythologize its subject, as is wont to happen in the immediate aftermath of a sexual assault allegation—a PR move to solidify gira as an icon before that title can be stripped from him (could they have landed on a more insensitive lyric for the title?). it isn’t particularly interesting, but it gets tedious by its second hour, as it pivots to the present day where swans is presented as some sort of therapeutic live music experience rekindling relationships between sons and fathers in the audience. much like pynchon, swans can be pretty unbearable in the present moment, but it never quite finds its way out of the unconscious.

5. IDYLLS, prayer for terrene there was a moment in 2018 when i got really into bands called IDLES and IDYLLS at the exact same time. sure, this coincidence foreshadowed my current lane in music journalism, which is specifically calling out similarities in artist names, but it also now feels like a fork in the road, a divine indication that i could either see where the indie rock lane takes me (even if it’s under the guise of working-class post-punk with a commendable political bent), or give in to the darkness of manic sludge metal and mathy powerviolence. i wound up reviewing joy as an act of resistance for post-trash (much to the polite chagrin of my editor, i recall, who clearly foresaw IDLES as the neutered derivation of USA nails they sort of were) and even revisiting the record at the end of the year to anchor a piece on 2018 as a uniquely wholesome cultural period.

since 2020, though, nearly everything i’ve listened to has resembled prayer for terrene in some way. this record opens with “lied to,” a scene-setter if only in the sense that it introduces the influence of converge (kurt ballou co-engineered the LP) and deathwish’s low-end-focused take on hardcore-punk more broadly. spanning about a quarter of the record’s entire run time, the seven-minute track never once subsides as free-jazzing sax gets thrown around a heaving mass of noise rock paired with entity-like vocals predicting bands like portrayal of guilt. more so, the record paves the way for daughters’ resurgence in 2018; the like-minded post-punk malaise of you won’t get what you want—paired with my own malaise after a year of forcing myself to adjust to impossible living situations in a part of the country i grew to hate as a home—surely factored into my shift from pursuing inclusive hooliganism to dissonant nihilism. assuming you don’t study the tracklist too closely, IDYLLS appear to be way less problematic, too.

revisiting the record now, i can also hear how elements of my past listening habits feature prominently in these songs, especially as “lied to” shifts into the record’s nine subsequent tracks that blur together in their stronger adherence to screamo and powerviolence norms (the wilding-out sax stays in the mix throughout, though). among the more experimental cuts, “PCP crazy” almost sounds like a lost oh sees/ty segall crossover event, with the former’s punk and jazz influences (and nasty little guy vocals most prominently modeled on “i need seed”) melding with the toughness of the latter’s noise-rock stuff circa slaughterhouse.

i revisited that IDLES album a few years ago, by the way, and cringed through nearly every minute of it. chalk it up to me andy-dropping-woody-for-buzz-meme-ing daughters and a vast buffet of politically progressive metal into my rotation, too much time online, or the brain smog gifted to me by my hollywood apartment, but these days i’m 100% team IDYLLS.

4. open mike eagle, dark comedy two of my favorite rap releases of 2024 were mixtapes by denzel curry and playthatboizay—the latter being a rapper who not only appeared on denzel’s release, but who also featured that exact collaborative song on his own record alongside featured guests almost entirely lifted from the king of the mischievous south sessions. zay’s tape dropped almost immediately after zel’s, and even zel’s tedious re-release campaign months later revisionising the mixtape as a proper album with added tracks was duplicated by the zay. it feels like artistic little-brother behavior that would be embarrassing if it wasn’t weirdly endearing.

given that open mike eagle is such a singular voice in hip-hop at this point, it’s funny to recall that he, too, briefly little-brothered veteran emcee/producer busdriver a decade ago (well, i guess dark comedy technically hit shelves a few months before perfect hair did). mike has never been shy about sharing his influences, and driver’s brainfeeder era can be heard literally (in its production and backing vocals) and figuratively (similar balance of humor and social consciousness) across this record, which as a whole presents a similar leap in cool confidence for the artist. there’s even plenty of overlap in the production credits—which hew closer to what busdriver had been doing leading up to 2014, whereas mike had largely been self-producing more lo-fi, minimalist beats—while OME’s similarly self-deprecating monotone can be heard rapping about his own son dunking on him for lacking busdriver’s economic lyricism on “qualifiers.”

although he’s veering into busdriver’s lane on dark comedy, i do think everything that made perfect hair stand out to me is done better here: the lyrics are consistently funnier and generally more quotable (“because everybody’s unemplooooyed”; the entirety of hannibal’s verse about compact cars) and its softer edges are more affecting. OME feels like a more natural fit for the middle section of the venn diagram forged by turn-of-the-decade internet-centric hip-hop between the transfixing dumb-guy raps of das racist and the offhand whimsy of serengeti, turning the record’s themes of contemporary artistry, modern technology (his comic-cronenbergian vision best displayed on “informations,” featuring one half of das racist), and a resulting economic instability for artists into a thesis statement without ever explicitly connecting the dots for us. just look at the shot-chaser pairing of the goofy satire “golden age raps” and the earnest reflection of “very much money” that follows it.

what’s most impressive about this era of OME is the way he manages to engagingly rap about nerdy past times at a moment when proud marvel fandom went mainstream without sounding particularly thrilled to do so—instead he makes these songs relatable without instilling a sense of self-loathing in the listener for, say, loving the spin doctors, as he confesses on this record’s complementary EP. it feels like a similar balancing act to introduce the record with a deluge of humor until, following a song named after jon lovitz, he pivots into more foreboding territory on the woozily psychedelic tour diary “idaho” (as kenny segal delivers a more memorable instrumental here than he did on perfect hair) and with jeremiah jae’s panicked glitch beat for “history of modern dance.”

the closing track hits the introspective emotional peak i suspect busdriver was searching for on “motion lines.” i recall it feeling completely out-of-character for OME at this point, even if it may have ushered in his forthcoming era of solemn autobiography and reverence for the history of hip-hop. every so often the instrumental for “big pretty bridges” gets stuck in my head—chipmunk-soul vocals, reverberating piano, and blown-out industrial sounds—and i have a hard time placing it. maybe it’s because it’s the only moment on the album where the music is more mesmerizing in its laid-back quality than the shyly intoned bars about sinus troubles and quaaludes.

3. odonis odonis, hard boiled, soft boiled my biggest takeaway from music across all genres in 2024 is that we need to start bullying artists for releasing double albums the same way we needed to start bullying nerds again prior to the ever-expanding sheldon-verse taking off in the early 2010s. to me it just feels like yet another infinite scroll, like content overload, now that the concept has been co-opted by major-label pop. as exhibit A proving that ambitious two-act productions can be reduced to a mere 35 minutes, odonis odonis’ jekyll/hyde sophomore album hard boiled, soft boiled contains two distinct halves that each individually contain their own unique universe of sound and swagger: the former a noise-rock opus of oozing libido, its yanging back half an introverted dream-pop wormhole directly contradicting everything we’ve just heard in both sound and personality.

after an ambient prologue, the OO machine quite literally revs up on “are we friends,” an aggressively cocksure industrialist post-punk manifesto putting their prior album’s surf-punk inflections firmly to rest while featuring lyrics that eschew innuendo for straight-to-the-point conjecturing matched only by the kid from the “so no head?” vine. from its opening kick drums to its screaming climax, the track establishes the album as being the product of the same toronto scene that wrought METZ and KEN mode, albeit with a certain darkness and industrial terror i’ve always hoped to find in trent reznor’s music. the ensuing “order in the court” is equally confrontational, swapping noise-rock for les-savy-fav-flavored sasscore, replacing its jarringly salacious lyrics with weird legal entendre and its sputtering machine ambiance with a downright abusive blastbeat breakdown.

after dipping into the blown-out shoegaze of APTBS, the mid-album “mr. smith” foreshadows the soft boiled half of the LP as distorted-to-shit acoustic guitar passages and distinctly mid-’10s ooh-ing shine through the noise, harnessing the sensation of busting out of the club into unanticipated daylight. that shift takes the form of atonement and sobering self-realization lyrically while the shoegaze and space-rock these words are set to feel as reflective as the first half of the record is impulsive, painting a portrait of the uncomfortable lyft ride home. “angus mountain” brings back the programmed drums with an unexpected beat drop while subtly implying a gradual deprivation of gravitational pull. the extended ambient “transmission” interlude and its sounds of mission-control radio chatter, then, set the scene for the closer and its full-on stratospheric dream-pop backed by a drum beat out-spectoring the ronettes before the track supernovas into an abstracted reprise of “angus mountain.” and also rapping?

which is all to say that there’s a double-LP’s worth of ideas crammed into these 12 reasonable-length recordings. it’s fascinating both structurally and thematically, while each song contains its own set of lyrical and instrumental surprises without ruining the linearity achieved with the help of the record’s ambient passages. it’s been a little disappointing watching this band settle into fairly straightforward EBM and coldwave influences after their first two records fused together so many disparate ideas, though i imagine everything i’ve just written was a hard sell for potential labels and audiences in the early stages of the music industry’s content-centrism.

2. moodie black, nausea for a decade now i’ve been debating what moodie black’s final form is between 2013’s industrial pop-rap, nigh-apocalyptic self-titled EP and this entirely dystopian slab of no-wave rap released 14 months later. but with every passing year, as the noise-rap canon further congeals around two particular figures, this release—effectively outlining how kanye is nothing but an ungrateful tourist within the subgenre and death grips is just the latest among a revolving door of hype-generating figures traipsing a world moodie black helped create without ever really getting credit for it—feels more essential. the duo literally purchased the domain name “noise rap dot com” well before that latter project even existed, while nausea featured a track called “wolves” a few years before ye released a much worse song also called that.

but beyond the explicit shots at the previous year’s yeezus and its blasphemous ego-raps (ratking also curiously catches strays alongside a mention of DG), nausea is a condemnation of the culture that bred a figure like kanye as it depicts a desolate wasteland which, when the camera pulls back, reveals itself to be LA. there’s clearly something of sole and the skyrider band’s post-rap vision of our world picked clean of resources by hypercapitalist greed here, although the focus is more attuned to the image of a society continuing to watch jimmy fallon as the world burns around us. in a sense, MB’s vocalist, K, seems to be indicting herself here, too, as she mumbles petty rap beefs as if it’s business-as-usual over fairly unsettling, dry-canteen, texmex-flavored instrumentals composed of a lone twanging guitar, a heavy-yet-minimalist beat, and a leitmotif of figures screaming and moaning buried in the background—a dichotomy which ultimately creates the same unspoken feeling invoked by sartre. or seinfeld, for that matter.

while the tone is obviously different, it seems appropriate that K adopts the surname of kafka’s protagonist to seethingly navigate these nightmare scenarios, less bureaucratically labyrinthine than transparently upside-down. in defending their turf musically, MB never reiterate the aesthetics explored by death grips or kanye, but instead venture into the equally cliche GY!BE (and, by extension, 28 days later) and david lynch (and, by extension, his industrial photography)—neither of whom have ever been adapted to hip-hop so fluently. the record’s uniformly subdued tone really only wavers when it momentarily livens up on “white buffalo” and “mollyap,” two tracks i imagine were included to hold listeners’ attention through to the album’s final, startling payoff that feels like the musical equivalent to the act of self-immolation it describes.

i’m sure K would argue that neither the self-titled EP nor nausea represents the band in its final form—if not because it’s an artist’s duty to always shill for their newest material, then because moodie black has since become something much queerer, more explicitly trans, over the years out of a sense of necessity. even if this project may never achieve its rightful place within the noise-rap canon, K seems intent on inspiring a more inclusive future for the suffocatingly masculine subgenre.

1. nothing, guilty of everything outside of genre, one of the biggest trends i’ve picked up on in music at the tail end of the ’00s was the shift from same-y pockets of revivalist indie rock to an explosion of ideas that appealed to the same audience, albeit an audience that was much more inured to the internet by that point. the two artists that most clearly define this shift are animal collective and death grips, two bands widely hailed as genius innovators at the time who also happened to attract clinically-online fanbases that denied any other artists from experimenting with similar sounds. i’ve written about the merriweather post pavilion ripoff phenomenon in the past, while i still encounter negative comments about contemporary noise rappers in user reviews and chat boxes. (did you read the blurb directly above this one?)

i think more broadly, the 21st century began feeling like a dead end culturally by the early 2010s, as we’ve continually recycled bygone eras of fashion at faster and faster intervals. tech hasn’t given us anything that’s improved our lives—let alone not made them actively worse—for quite some time, and music has only pushed forward occasionally, with the ill-fated dubstep and stomp-clap movements being touted as the future a decade ago. yet all the best rock music being celebrated on year-end lists in 2024 takes proud aesthetic cues from ’70s folk rock, ’80s new wave, ’90s grunge, and ’00s pop (and, incredibly, even nu-metal—truly proving that we’ve hit the bottom of the barrel), repackaging old ideas for fresher songwriting sensibilities.

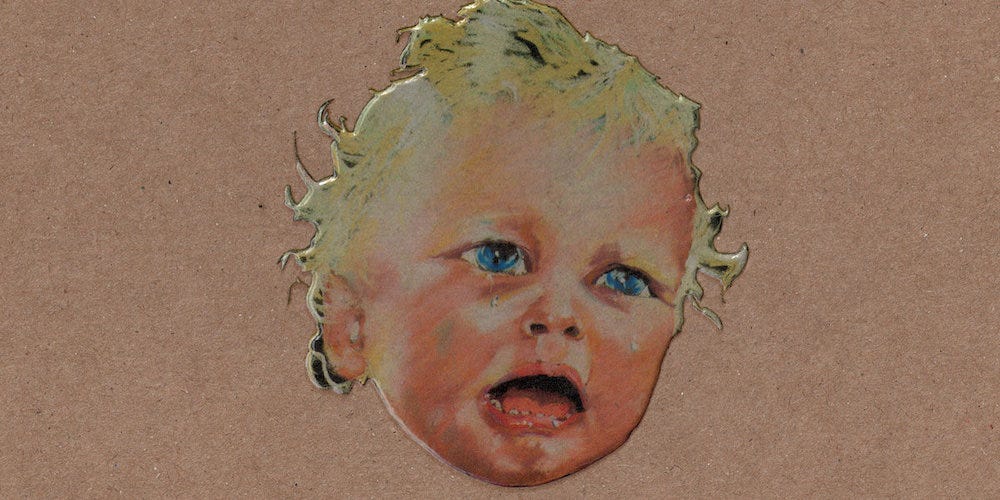

you could make the case that that’s also what domenic palermo did when he wrote guilty of everything, an unabashed shoegaze record released during the brief 15-ish years between shoegaze’s initial wave of popularity and its recent resurgence. as the lore goes, the hardcore-scene lifer palermo had just spent time in prison on charges of attempted murder (in self-defense), where he realized his only two paths forward were suicide or to start a shoegaze band, having grown up in a household soundtracked by MBV.

yet in ultimately doing so, what set his new band apart from recent pop-punk crossovers like title fight or metal trailblazers alcest (or even my bloody valentine’s own return LP) was the fact that carnivorous reverb wasn’t meant to be the emotional focal point of these songs. instead it was the end-of-one’s-rope autobiographical lyricism written by someone who even at that point had endured more tragedy in his life than most bands outside of the gnarly east coast hardcore-punk circuit could fathom, stripping away the nostalgic appeal and vintage-fetishism inherent to the genre to write streamlined riffs that only serve to complement palermo’s stark capsules of guilt and grief and loathing, of being lost amid the endless-ocean-in-all-directions that is hitting 30 without any clear direction in life.

half of the brilliance of guilty of everything was palermo’s choice to forgo his history of harsh vocals in favor of fairly conventional shoegaze wisp, a sense of weightlessness that reflects the walking-ghost persona he’d taken on in his personal life as he felt that he’d outlived his usefulness (“crucifixion seems noble / when paradise is hell,” he exhales to open the record). this is in direct contrast to the music, which foregoes the shoegaze traditions of apathy and imperfection in line with ’90s alt-rock’s turn toward slackerism—or even the more recently chic irony epidemic.

these songs are all unexpectedly tough, further intensified by crisp, hi-def production that contrasts with the genre’s penchant for tracking lines and hazy renderings—as if it, too, is mulling over the lyrics’ themes while completely sober for the first time. the back half of “somersault” introduces their most impressive balance of massive post-rock instrumental climax and sighed vocals, while “bent nail” argues that the band is equally adept at the breezy dream-pop heard in the track’s opening as they are at the relatively gentle hardcore breakdown that closes it, foreshadowing significantly heavier, lyricless drops later on in the record.

10 years later and even the moments i recall being the album’s weakest feel packed to the brim with emotional storytelling, despite the vocals not really selling it. i’m thinking of the gothic film caked over “endlessly,” which further drags this album away from the tradition of shoegaze while being so subtle that it doesn’t feel like a bid for establishing entirely new sounds in the way that MPP did. the album’s metal-centric record label only bolsters any claims that guilty of everything wasn’t intended to usher in this current chapter in shoegaze that significantly expanded the genre’s definition to include everything from black metal to tiktok-sourced teen bands poached by major labels, as does the utter bleakness of just about any isolated lyric found within these nine songs.

but as the record’s dramatic close teeters on the brink of total desolation, its barely-perceptible first ray of hope can be found in palermo’s vocals as they’re layered for the first and only time on the record, making him seem less alone. guilty of everything’s legacy feels equally like a coin toss, as it seems to have preceded all kinds of fascinating modern interpolations of shoegaze yet to be explored within similarly heavy sonic terrains as well as just as many regrettable bastardizations ensuring nugaze’s imminent demise. and this record may very well be guilty of paving the way for all of it.